[ 63XC.COM | SPATTER | RUCKER ]

My Adventures at Dover

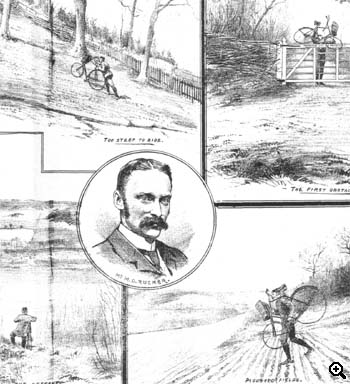

Mr. Rucker forwards us the following interesting description of his experience with a safety bicycle during the recent volunteer manoeuvres:--"I fear," he says, "it is somewhat presumptuous of me to attempt to write upon the subject of cycles for military purposes, as I am not a military man myself. The experience I have I gained at the Easter manoeuvres. This, however, is, I think, sufficient to enable me to correct some of the erroneous opinions expressed by cyclists upon this subject. "A good deal of diversity of opinion exists upon the cross-country test performed by me under orders from HRH the Duke of Cambridge. Some say that the test had neither 'rhyme nor reason'; that it was ridiculous to expect that a cyclist would ever be required to leave the road, and that if he were, he would find it easier to deposit his machine and cross the country on foot. You, Mr. Editor, compared me to Kaufman, and asserted that no other member of the scratch corps could have succeeded in surmounting the obstacles. I must beg to differ from you. I honestly believe that any one in the corps could, with very little instruction, have gone over the ground. Very few cyclists have ever had occasion to go across country, and therefore the majority of them have no idea what can be done in this way. My experience in this sort of riding has told me that there are very few obstacles that can be surmounted on foot which cannot be overcome on a bicycle. "In order to give your readers an idea of the kind of country chosen for the test made, I have recently gone over the ground with your artist, and the sketches given are in no way exagerated, as you can see, sir, from the photos I enclose for your inspection. In order to prove that any rider could get over the difficulties encountered without either being able or willing to ride over the whole of the ground, I induced a local cyclist and reader of the 'B. N.' -- Mr. Hambrook -- to accompany us on his bicycle. He has been a rider for less than one year, and succeeded in following without any assistance. He said he should not have thought it at all possible to take any bicycle over some of the places. But he had had no occasion to go across country before, and had no idea a cycle was for this work, and I think it would take a very stiff obstacle to stop him now. "When I left the Duke I had half-a-mile of road to traverse before pushing became necessary. A similar extent of good road lay at the other end. So in spite of the delay caused by having to lift the machine over gates &c., I think I should have beaten any infantry, though impeded, too, with accoutrements, and no horses could have gone over the ground at all. "No doubt, sir, some will remark, 'What good can this do to the cause? Is it likely any work like this would be necessary?' I think it is quite likely. The notion that cyclists should act as cavalry and oppose cavalry is, on the face of it, absurd. The cycle can only be used to convey men quickly from one point to another, and when it comes to actual fighting, cyclists would be no better off than infantry, excepting that they would be able to retire rather more speedily (if any British soldier ever resorts to this method of extricating himself from danger). "My notion is that cyclists would be of immense value as messengers or scouts. Suppose a message had to be sent from the commander of one regiment to another, and the cyclist found that, to reach the desired point, he would have to leave the road, and, in order to deliver the message quickly, would have to cross ploughed fields, and climb several gates and hedges. Would it not be better to take the machine with him than leave it behind, even if he had to carry it all day? I think it would. It might be necessary for him to return by another route, or proceed with the regiment some distance, before he could get the reply. "Then again, when scouting or sharpshooting, he could not always remain on the road, as it might be necessary for him to take shelter in some wood or building, and he must have his machine with him. "Whilst tricycles might be useful in some ways, I think bicycles would be preferable for many reasons. They require only a few inches to run on, whilst tricycles require about three feet in width, and unless the roads be fairly good, tricycles would be only encumbrances. Safeties, I believe, will be the machines chosen, though if riders in this country, as in America, are not allowed to attempt a journey until they are able to do such things as in this coutnry constitute an exceptionally clever rider--in other words, till they are thoroughly masters of their steeds--they will not, on this account, be very profitable, certainly. Moreover, if a theatrical effect be desired, that is to say, if the machine most readily adapted for drilling is to be selected, ther can be no two opinions. "Not knowing what kind of work I might be expected to do, I took a 'Beeston Humber' safety. Nor did I regret my choice. An ordinary bicycle would not have been so handy for carrying about. I heard, too, that I might have to sleep in barns or such-like places, so I carried with me a large bag containing a complete change of clothing, and also a large waterproof coat. These could not have been stowed on an ordinary. From the sketch of the ploughed field it will be seen how easily a safety is carried. The cross-bar comes over the shoulder, and with one hand steadying the front part, good pace might be made. I may say I have in this way carried a machine comfortably a mile in 7 1/2 minutes. "I fear, sir, that this letter has over-run your limits, so, much as I should like to relate some of my experiences on a cycle, I must conclude these notes with assuring your readers that we had a 'real good time,' and that everyone derived considerable benefit from the first attempts at making use of the cycle for war purposes."

[ TOP ] |

Date

v1.0 appeared in Bicycling News, May 7 1887

Related

Bob French, librarian of the V-CC, dealt kindly with a request for material on 19th century offroaders, and made high-res stats from the original magazine at very short notice.

The 'ordinary' bicycle to which Mr Rucker refers is what we would now call a penny farthing or high wheeler. The 'safety' is like a modern bike, with two wheels of roughly equal size and chain drive to the rear. And it's a fix.

Mailing list

Join the 63xc.com list.