[ 63XC.COM | HOW TO | THURSDAY ]

Frame Geometry and Design: A quick take

My name is Thursday. I ride bikes, I build bikes. Some time ago, Will asked if I could write something on frame design. As with so many things in my life, it has taken a while to get to it. (Sorry 'bout that.) I was going to write about geometry, but I realized that geometry can't be understood in isolation from the issues of frame fitting and the applications to which the bike will be put. Geometry, frame fit and application are the three points triangulating a good bike design. A lot of the rest is design process: it is an art, but one that requires discipline and the ability to make sense of one's experience. I am writing this for those of you who are restless and dissatisfied with easy answers, whether it is about bicycles or other things in your lives. I take a narrative approach to design. Every bike has a story behind it. The process of design is the process of uncovering that story, and then working out what to do about it. So I guess the place to start is with the story of how I got to be a bikebuilder. This is my story, but it could be yours. It all started when I convinced my wife 'we' needed a set of oxy-acetylene torches so I could weld the fenders back on our Volvo. As it turned out I did just that, but I had some other matters on my agenda as well. One of them was the ability to modify bicycle frames. Or maybe even make them. From there, it all kind of snowballed. I fixed a loose brake bridge. Then I put rack mounts on all my bicycles. Then shifter bosses. Hey, how about a couple extra water bottles? Then I found a Raleigh ladies' 3-speed frame in an alley in Phoenix and made a kind of limp mountain bike before converting it into a Muttonmaster. And then my friends wanted me to modify bikes or make new ones. And then there was that Peugot U08 that turned into an indescribably ugly magenta je ne ses quois... Every last one of those bikes was weird in some way or other. I started copying frames. Like that Shogun mountain bike that got reconfigured with a sloping downtube, turning out pretty well... On it went. I was picking up bike company handouts, spec sheets out of Performance and Nashbar catalogs, anyplace I could find a set of frame specs. I would use them to build. If it was in the book it had to be right. Right? I guess it started coming together for me the time I proposed a mod on a nice little Japanese frame for a small woman rider in Albuquerque. I looked at all the small frames in all my spec sheets and proposed to chop this cute 46cm Kawahara into the 'right' geometry and proportions for her. It was to have been a pretty radical chop, swinging the 72 degree seat tube forward and lengthening the front triangle. The stays were long, too, compared to the Italian bikes I'd seen. Idly, I wondered how the Japanese could have gotten the geometry so far off on that frame. Then I got a look at a small man riding a 48 or 50cm frame down the street. The guy was having a ball, the frame fit him perfectly, short legs, long torso, long hairy arms, big head and all. The prospect, by contrast was a perfect miniature woman, proportioned like a model, just smaller. I thought about her, looked at the man. A light came on. I ran back to Window Rock and measured the Kawahara again... it was made for her. I called her and told her she could have the bike cheap 'cause all it needed was paint. And I had a can of this lipstick-colored magenta kandy with blue pearl. Understated elegance. She took a pass on the frame and decided instead to get a used 48cm Italian something-or-other. Said she was getting a deal she couldn't pass up. I never heard from her again and often wonder how it all worked out. I started really looking at people, especially where I could get a bunch of them standing around together. Where are their beltlines? People the same height could have a half a foot difference where they belted their pants. I noticed some people's hands hang almost to their knees, while others' are closer to their waists. I saw as much variation in women as in men and started thinking about dachshunds and gazelles and a range of body types in between, rather than stereotypical 'male' and 'female' shapes. Tailors and dressmakers develop the same kind of eye. You think they are checking you out, maybe admiring you, but in their minds they are just cutting cloth. One of my friends makes coffins and she sometimes gives me that same appraising look. I changed my method of frame sizing. The only thing I was still doing by the book was setting the seat tube angle. I used the old method of dropping a plumb line from the rider's knee to the center of the pedal axle with the crank at 3 o'clock. The rest of the sizing numbers come from the rider's own story. Does she use a lot of ankle pedaling? The seat tube will be longer and maybe a little more upright. Back pain or neck pain on the current bike? It could be too long in the cockpit, or too short. Try to analyse their riding position. There is a narrative, but it is written in body language. What is the story? Next, I started looking at different riding styles. I found surprising variation. Crit riders and time trialers liked to bunch their bodies up on the smallest frame possible. Century and other long-distance riders liked to stretch out, calling for bigger frames with more positioning options. Touring bikes had to be low enough to accommodate the tourist's flat-footed standover, but they also had to cope with the rider 'growing', stretching out on a long tour. Then I started looking at riders who 'just ride around'. JRA means something different to every rider. A rider with back problems may like an upright position, meaning a short front triangle, flat bars and maybe a somewhat steeper seat tube... or maybe not. Some urban riders will pick the biggest frame possible. Look big, ride big, be seen, dominate. Others preferred smaller frames so they could hurl themselves through the interstices of traffic, taking to the sidewalk as need be... scattering pedestrians like geese before wolves... oh, hell, you get the picture. And that's just road bikes! I had always been more or less a roadie, but I had a pretty broad definition of what constituted a road. Until I started making my own frames I had to ride what I could get. I really liked vintage Raleighs and Schwinns, but would ride anything with two wheels. That all changed when I started making my own frames. It did not take long before I realized that a lot of production frames were kind of crappy. I really thought I could do better. I was a legend in my own mind. My first frames were like my early mods -- by the numbers. Once I got over the initial buzz of riding something I'd made myself, I started noticing things. There was the vague, dead feel of my mountain bike, and the sloppy way the magenta 'thing' would turn to mush when I got on the pedals hard. Newly critical, I started trying out bikes in shops and found the same flaws, even among the best brands. Some of these were bikes that got killer reviews in the 'zines. I wondered if there was something wrong with me, or if they were testing different bikes from the ones I was riding. Then I saw an early Bontrager frame in a shop in Flagstaff. It looked right: small, light, almost BMX-like with its short front end and low sloping top tube. Keith's bikes were famous not only for their handling and light weight, but for staying in one piece under hard use. That seemed like a good mark to aim for. I built a couple of nice mountain bikes on the Bontrager pattern with Reynolds tubing, sold one and rode the other. It was better. I had misjudged the angles a bit and ended up with a wicked fast-handling front end. I got to like that quickness. The bike was stiff laterally but had a kind of springy, compliant ride. A lot of things came together for me on that bike. A lot of it was happy accident and dumb luck. Meanwhile, the aluminum revolution was on and mountain bikes were getting worse and worse. I literally could not give away a handmade steel frame. Out on the trails I was not as fast a rider as the young guys on their new brand-name alu bikes, but I could get through a technical situation really well, and I would finish a ride feeling good enough to go out and party. The alloy riders would be all in. About this time, Roman Bitsuie asked me to build a BMX bike for his son Beau. I looked at some bikes, got some numbers and built it. Beau liked it and rode it everywhere. That got me interested in BMX bikes and I built a couple more, including a beautiful little 531-framed 20 incher. I took it to a track in Albuquerque and got some guys to try it out. Most of what they said went right past me. I gathered the bike was OK, but it was all in BMX-speak. So I built a bike for myself and signed up with the ABA. Long story... for another day. What was important was that I learned a whole new way of riding. It was like my body learning a whole new language. After that, the BMX-speak started to make sense, the words coming into alignment with the actions, events and sensations they signified. It was an eye-opener to ride a Kastan-designed Mosh 20-incher. This was a bike with a radically short rear end, designed for the 'technical' tracks that were being built during the BMX resurgence of the 1990s. The Mosh gave a whole new meaning to the concept 'lively'. You put it to the pedals and that bike would leap right into the air if you weren't careful. I went back to the CAD program and redesigned all my BMX bikes. I came up with a 24-incher made from 531 mountainbike tubes. It weighed less than four pounds. It was a great bike to ride around, and would fly into the air on any kind of an obstacle. I raced it a while, then wrapped it around myself the first time I cased a jump. That taught me not to use a light tubeset on a BMX bike. I ended up using Reynolds 525 in a 31.7mm/35mm toptube/downtube configuration. It was actually cheaper than straight-gauge tubing, and I've never had one come back broken from a race. It took several years to get the formula just right on the BMX bikes. As I got stronger I realized the frames needed an incredible amount of lateral strength. I started using 7/8" (22.2mm) chainstays and 3/4" (19mm) seat stays, bent from aircraft grade chrome moly tubing. I kept the rear ends tight, sizing the front triangle to be a little short for me. The tubing combination worked out quite well, building up into a bike with just enough flex to be snappy, giving you an extra kick on a jump or coming out of a turn. I hadn't really been thinking about weight, but these steel frames were actually lighter than most alloy BMXers. BMX frames are tiny compared to road and mountain bikes. How, you ask, does an adult ride such a thing? Go to a race and see! Even though there is a seat, riders spend the entire race out of the saddle. Their bodies are all over the bike -- mass centered between the wheels pedaling, butt over the rear wheel pumping through a rhythm section or setting up for a jump. One of the basic BMX moves is called 'manualing', where you pull the front end up off the ground. If you can manual you can jump. It takes a good deal of upper body strength, and the bike has to be sized just so. If it's too long in the front end, it won't manual. Too short and the rider gets his body mass too far forward and cases a landing. Too short in the rear end and the bike 'loops'. A good exercise for the aspiring BMX framebuilder: watch a rider on the track, measure the frame she is riding, then figure if the frame length forward or back needs correction. I started building BMX bikes with slow steering so they would straighten out if I got in trouble on a jump, and low BBs for steadiness in the gate. I got out on the track a lot. As I got faster I found that I was going high on turns and was not getting out of the gate as well as the other riders. And the relatively long front triangles I was building were keeping me from using my body weight to the best advantage on jumps. The geometry evolved and eventually I standardized my BMX models. It was rewarding to see GT adopt 'radical new geometry' for their year 2000 'box' pro BMXers that mirrored what I had developed two years previous. I applied what I had learned on the BMX track back to mountain bikes. As a result, I started to get a lot better on singletrack, especially in 'technical' situations. Now that I knew how a bike could handle, bikes with 'standard' geometry -- 71/73 angles, 16 3/4" (425mm) chainstays -- felt cumbersome. I started looking critically at mountain bikes wherever I saw them. Any time I saw a bike covered with mud, it seemed the seat was jammed as far back as it would go in the seatpost. The hard-core dirt riders were not sticking to the program. Next mountain bike I built had 72/72 angles and was a little shorter front and rear than its predecessor. It handled better, and even for a dachshund like me the seat position was right. The slacker seat tube angle meant that I had to run the seat a little lower to pedal efficiently while seated, but that was OK.

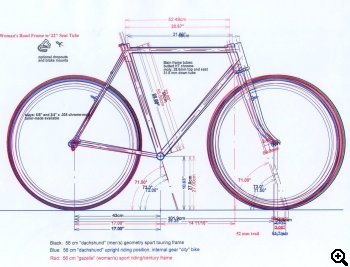

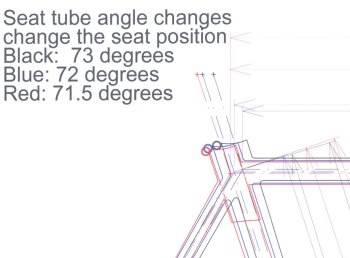

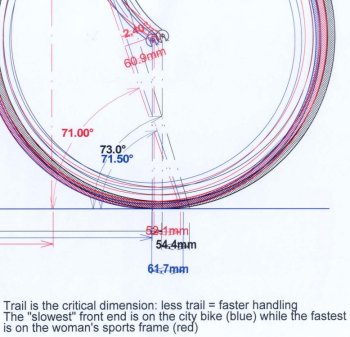

About this time, Dual Slalom got to be a hot event. It looked enough like BMX to get me thinking about adapting my BMX designs. The rule book said a DS bike had to have at least five speeds, so I had to redesign the rear ends to accommodate a rear derailleur and 135mm rear hub spacing. It seemed that there was a lot of variation in tracks, some fast and smooth, others gnarly and dangerous. I designed a big BMX bike, set up for what was then a long-travel dual crown fork. Then I put long horizontal rear drops on it, with about 1.5 inches (35mm) of usable adjustment. The fork could be adjusted up and down in its clamps to alter the steering angle from 68 to 72 degrees. The bikes were very fast, and a lot of them found use in extreme riding, freeride and even as light downhill racers. The feedback I got was that most riders slammed the rear wheel as far forward as it would go, 16 1/4" (412mm). One of these bikes came back twice with shear failures, once at the front of the toptube and the other time at the end of the chainstay. I realized the bike needed gusseting in these locations and have done that since on most of my frames. I have since seen the same distinctive type of failure on other lightweight mountain bikes that were ridden hard. No tearing or twisting of the metal, just a clean circumferential break near the headtube. The logical conclusion The experience with Slalom and BMX bikes kept eating at me. I was jamming my hardtail through stuff a man my age should probably leave alone. I started using a 26-inch wheel BMXer for a lot of technical and hardcore trails locally. I was also getting truly unusual orders for custom frames -- late night calls from people who wanted mountain bike versions of the 26-inch cruiser. After fielding a string of those calls I made a couple of custom frames for 'extreme' type riders. Everything was pointing in the same direction. After mulling over my thoughts for a year, I built a 'New Model' mountain bike, a mutant bastard cross between a cross-country bike and a slalom bike. It was light and had a full gearset like an XC bike, but it used a BMX tubeset for the front end, smaller 3/4" chainstays, specially bent to provide clearance for 2.4" tires, and it had the geometry and sizing of a slalom or 4-cross hardtail. Frame design: balance, technique and stability Dirt is good. It brings out the truth about the way a bike handles. On the road, you can ride for years without even realising that there's a problem with your bike. The tires grip so well that the any imbalance registers as a passing 'stiffness' or a 'loopy' tendency in the handling. Then, one day, you hit a little sand on a tight bend. Your bike loses its grip. You can't recover and the bike continues in a straight line to whatever fate awaits. Or you get on the pedals hard in a corner and the front wheel comes up in the air leaving you face skyward riding a unicycle to hell. These problems would have shown up in minutes on a dirt bike. Dirt reveals what pavement hides. Dual slalom, in particular, shows up handling and balance issues, and my slalom bikes really taught me about balance. The crucial issue here is cornering style. Roadies only know one way to turn -- railing it. Roadbikes have to rail, otherwise they're not fit for purpose. Railing requires perfect neutral weight balance between front and rear wheels. Dirt riders, on the other hand, have several options. Many choose to rail. Others favour near-unicycle turns. Here, the front wheel is loaded just enough to track, and all the rider's power and bite goes in the rear tire. This works particularly well in loose dirt. And don't let's forget the motorcycle turn: jam into the corner, steer the front wheel, break the rear loose and put down your inside foot. The M/C turn is a regrettably coarse technique for dealing with the typical ill-designed, understeering mass-produced frame, but it has its adherents. (It works a lot better on a motorcycle, where you can put your foot down and still have power at the rear wheel.) It goes without saying that, when you're choosing or building a frame, you need to know the kind of cornering it will be used for. Laying out a frame Let's say that we're dealing with a fully custom frame. The groundwork has been done properly, so we already know that the rider is in a terrific riding position: comfort, power endurance... Also, the rider has made their functional requirements clear, so the builder knows the rider's cornering style. What next? The BB has a huge influence on handling, so that's the next item on my list. A low BB gives a stable ride but reduced pedal clearance. A higher BB is less stable, but can be thrown into corners with confidence. On mountain bikes, high BBs mean better clearance and the ability go more places. On BMX and freestyle bikes a high BB means easy manualing and a faster start out of the gate. On road bikes, a high BB means a bike that can be laid into a corner without clipping or, worse yet, catching a pedal. Next, it's time to decide where to put the front and rear wheels. On a bike meant to be ridden in dirt, this is a function of the type of riding. In order to place the wheels, the builder needs an understanding of the rider's style. What cornering technique do they favour? Do they like to sit and pedal, or are they are all over the bike? Road bike builders have it easy, because they know where the rider's center of gravity is going to be most of the time. The only thing they have to worry about is toe clearance on the front wheel. (My own thought is that, when they're in riding position, the rider should be able to see the front hub just a little ahead of their nose.) With the front wheel in place, you can go on the rear. The normal preference is for a roughly 50-50 weight distribution between the two. You can get an idea of how it's working by setting up two bathroom scales under the bike's wheels with the rider aboard and in position. Generally speaking, 'gazelle' body types, with their light upper torsos and powerful legs, will need a longer chainstay to keep the front end down when it's trying to lift -- for instance, when pedaling hard out of a fast curve. 'Dachshunds' will want shorter stays to improve the balance problems caused by their top-heavy bodies. Dirt riders tend to favor a slightly rearward weight bias as well -- except for climbing, where they struggle simultaneously to keep the front end down and to keep the rear tire from breaking loose. Next on my handling checklist is steering geometry. The most important number here is 'trail', the distance separating the center of the tire's 'contact patch' from the imaginary point where the steering axis hits the road. As this number increases, the bike gets more stable. As it decreases, the bike gets more agile and twitchy. Road bikes usually have 50-55mm of trail, but I once I had a couple vintage Raleighs with just 38mm. This gave a 'light' feel, even to a 35 pounder like the Grand Prix. It also provided downright evil handling at speed.

Some frames, especially small ones with full-size wheels, need a shallow steering angle to get toe clearance for the front wheel. The normal solution is a custom fork. The builder bends ('rakes') the fork legs to fine-tune the trail at the front wheel.

Suggestions for starters By now your head is probably spinning. Is nothing certain? Is everything permissible? Are there no standards? We-e-e-e-l-l-l... yes! However, I do think that there is a kind of algorithm that riders can follow to get a really good bike, whether from a custom builder or a mass-produced brand. It's easiest with road bikes. Find a shop with a 'fit bike' like the Serotta and -- more importantly -- someone who really knows how to use it. A skilled fitter will be able to set you up with the reference points for your frame's cockpit: height, seat tube angle, front wheel clearance, and distance from saddle to bars. Once you get these numbers, try to find a bike that is close. Modify as necessary. Once you have the bike set up, you can lay out the bottom bracket height and the front and rear wheel centers, always thinking of function and balance. Then look for a frame that meets your spec, or find a builder who will work with you. On a mountain bike or dirt bike the starting point should always be the rider's current bike. My approach in these cases is: observe, listen, talk. It can be a bit like analysis! "Is your seat slammed all the way back?" "Do you need more standover height?" "What happens to you when you climb? When you corner? On descents?" "Do you feel a sense of maternal abandonment? How could she throw you out of her bedroom and let that man in?" Afterthoughts on bicycles and the human mind When talking about white society, the Navajo use a polite circumlocution: the 'Dominant Society'. The Dominant Society has power, wealth and can back up its dominance with violence if need be. It is a closed system that frames all discussion in its own terms. We are its products -- literally -- with our commodity education and our carefully groomed preferences and habits of consumption and life style. Is it good? Is it bad? Probably both. Who knows? We were human, literate and sophisticated before the rise of the Dominant Society. We were aware, in ways which I think have been educated out of us. We used our natural minds to engage the natural world. We all still have the natural mind lurking within us, buried deeper in some than in others. Bicycling exercises that natural mind. It is sensuous, exciting, mindless fun. At speed, our attention is focused, our senses taking in everything, our bodies acting seemingly by themselves. We go with the flow. We defy gravity and common sense. Our bodies know what to do -- this is what I mean by 'body knowledge'. Some of us can conceptualize and speak about these things. A few are able to use the power of the natural mind, subordinating our Dominant Society analytic methods and skills, to make something new and perhaps useful -- a concept, an object, a ruckus. A good custom framebuilder, I believe, is someone who has that combination of knowledge and skills, someone who is a bit of a Freudian analyst and a bit of a machinist. It is a rare combination. Some of you who are reading this have at least the human and natural-mind skills, and the body-knowledge, to do a lot of the design work for yourselves. You have to be able to tell your own story. I wrote this piece primarily to share with you the skills and knowledge that have helped me in my work. You probably already know what you need in a bike frame, you just don't know that you know. This is a subversive activity. Wake up, baby!

[ TOP ] |

Writer

Thursday trades as Thursday Bikes. His slogan: Why not start the weekend on a Thursday?

Date

v1.0 written May 2006

Related

Read Thursday on his Mutton Master sheep herding bicycle.

Mailing list

Join the 63xc.com list.