[ 63XC.COM | SPATTER | MTB RAH RAH RAH ]

MTB RAH RAH RAH

From its very beginnings, the technology of flight and rocketry had been in dialogue with the dreams of science fiction. By the late 1930s, the fin de siecle trailblazing of Wells and Verne had degenerated into the limp cliches of space opera. At the cutting edge of SF, mystical visions were giving way to practical engineering. Doyen of the new hard SF writers was Robert Anson Heinlein, RAH to his fans. Heinlein was the real thing, an engineer with contacts in the new aerospace and defence industries. The short stories he wrote for John Campbell and the novels which followed gave science fiction a new voice: optimistic, outward-looking, hard-headed. As we grasped at the century's dreams of flight and power they turned to ashes in our hands, every one of them. For the kids growing to adulthood today, the moon landings are a phantasm from the era of 8-track and 425-line, an analogue memory which loses something in the conversion to digital. It's no coincidence that RAH's most enduring works have been the ones he wrote for an earlier generation of children. Heinlein churned them out in the 50s, targetting an audience too young and too drunk on possibility to offer any real criticism. The publishers kept them in print, year after year. I turned them up two decades later, a neat row of innocuous-looking hardbacks in my local library. The Green Hills of Earth, Red Planet, Farmer in the Sky, Citizen of the Galaxy... By the mid-60s, telemetry from the first interplanetary probes had already given the lie to Heinlein's Venus of teeming swamps, his intrepid colonists breathing the thin air of a Mars criss-crossed by Lowellian canals, his interplanetary menagerie stocked as richly as that of an Elizabethan adventurer. Had I but known it, the vision I was buying into was as defunct as any of the previous century's utopias. But even the most anachronistic hard SF had its consolations. Heinlein offered gauntletted spacesuits, prismatic and gyroscopic navigation systems, electrical circuits embedded in protective lucite--almost-material goods, things you could imagine hefting in your hand, tainted with the unmistakeable hydrocarbon whiff of the real. And there were bicycles. In Heinlein's solar system, prospectors roam the Martian deserts and mine the larger asteroids. They are wildmen, bearded solitaries, gambling years of their lives on one good strike. They ride bikes of a particular type: robust, dependable, with outsize tubing, wide handlebars for control, and big tyres for uncertain ground. Here's a prime example from Space Family Stone (1952): ...on both Mars and Luna prospecting by bicycle was much more efficient than prospecting on foot; on the moon the old-style rock sleuth with nothing but his skis and Shanks's ponies to enable him to scout the area where he had landed his jumpbug had almost disappeared. All the prospectors took bicycles along as a matter of course... ...deprived of his traditional burro [the prospector] found the bicycle an acceptable and reliable, if somewhat less congenial substitute. A miner's bike would have looked odd in the streets of Stockholm; oversized wheels, doughnut sand tires, towing yoke and trailer... ...not the vehicle for a spin in the park, but on Mars or on the Moon it fitted its purpose the way a canoe fits a Canadian stream. Sound familiar? The pioneers of the mountainbike movement were science weenies. And they're a decade and more older than me, teenagers of the 60s, space cadets. They must have read Heinlein. Perhaps, in spite of everything, one of those midcentury dreams of escape really did come true. I'd like to think so. [ TOP ] |

Date

v1.0 written July 2003

Related

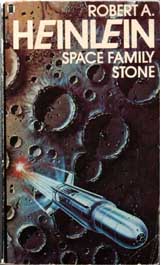

Ian Dodds at Darkwood helped me to dig out the NEL edition of Space Family Stone which I remember from my childhood, although the blast from the rocket on the cover is now red rather than cool green.

Mailing list

Join the 63xc.com list.

These days, you'd search a long time before you found a kid thinking seriously about space stations, interplanetary travel, colonies on Mars. It wasn't always so. The space program suffused the culture in which I grew up, whispering wild promises of freedom to anyone who would listen. Many of us did.

These days, you'd search a long time before you found a kid thinking seriously about space stations, interplanetary travel, colonies on Mars. It wasn't always so. The space program suffused the culture in which I grew up, whispering wild promises of freedom to anyone who would listen. Many of us did.