[ 63XC.COM | STORIES | TOUR OFFROAD ]

The Tour considered as an offroad bicycle race Earlier this year, I read a superb book on the Tour. It's called 'The Unknown Tour de France' and it's written by a guy called Les Woodland, a long-term cycle journalist and Tour follower. I'd love to do a full review, but can't really justify it: the book is five years old, and at least two thirds of it is devoted to well-documented shenanigans that took place on the paved and re-metalled roads of post-war France. Roadie stuff, in other words. But the first third of the book is different. The early Tours that Woodland recounts are passing, as histories must, into the realm of myth. Thus they become part of a common cycling inheritance, and fair game for a 63xc.com article. Like many myths, these stories are often hysterically funny. From our remote perspective, informed by the broad-spectrum media and slick commercial mechanisms of 21st century sport, the Tour's beginnings resemble a slapstick silent directed by Mack Sennett. Did Maurice Garin and the other big names of 1904 really secure their lead en voiture? Did it really take gunfire to drive the baying pro-Payan mobs from the course in Nîmes? Did Henri Desgrange really do that to Major Taylor? (Joking aside, if you own one of those T-shirts with the Desgrange quote about pignon fixe, you might want to read up on Henri's politics before you wear it out again next summer.)

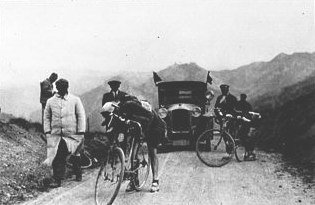

More to the point, those first tours are played out against a backdrop familiar to readers of this site: that approximately fin de siècle period when horses gave way to cars and lorries, and, for a few brief years, the cyclist was the fastest thing on the (rough) road. The Tour was one of the first events to make riders into heroes. There are four of them. Their legs, like giant levers, will power onwards for sixty hours; their muscles will grind up the kilometers; their broad chests will heave with the effort of the struggle; their hands will clench onto their handlebars; with their eyes they will observe each other ferociously; their backs will bend foward in unison for barbaric breakaways; their stomachs will fight against hunger; their brains against sleep. And at night a peasant waiting for them by a deserted road will see four demons passing by, and the noise of their desperate panting will freeze his heart and fill it with terror. Henri Desgrange, quoted in 'Unknown Tour' A succession of writers commencing with Barthes have detected in the Tour's implicit code -- travel as travail, perhaps -- the stirrings of a particular kind of nationalism. Certainly, it is impossible to read the overheated prose with which Desgrange announced his brainchild without hearing echoes of that other, more sinister rhetoric which would flare into popularity across much of Europe in the decades to come. (Note in particular that cowering peasant.) Woodland, however, is a truly English pragmatist, and he counterpoints hype from the press office at L'Auto with telling details of the day-to-day life of the Tour: boils, liniments, amphetamines. He gives a voice to that band of hardnosed professionals who quickly came to dominate the event and who consistently failed to view its increasingly ambitious traverses of the French patrimoine in ideological terms.

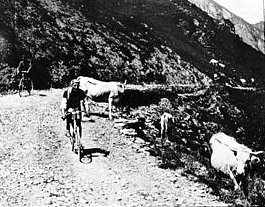

We chatted for a while and then, rather shyly, he said he'd ridden the Tour de France 40 years earlier. Well, that was in the 1960s, so it'd have been the 1920s. I said the roads must have been very different, and he said "Oui, monsieur, they were very rough surfaces then." I pointed at the way the riders would be coming and said I'd seen the climb in the days of Bobet and Coppi, when there were holes in the surface and stones and rocks on the road. Now, of course, they're in a very good state, more or less smooth like any other road. And he looked very surprised and he said "Non monsieur, you don't understand. We didn't come up here." And he turned and pointed at a tiny goat track behind us, all rocks and tufts of grass and no more than a few yards wide. "We came up that road there!" Alan Gayfer, editor of Cycling, ibid Of course, for the testimonies of those like that forgotten cyclist to be given due weight, the investigating journalist must attempt to convey their experiences as completely as possible. Woodland doesn't disappoint, devoting six whole pages to the cycling technology of the day. (That's six more than Roland Barthes managed, fact fans.) Three of them go to a French bike, reputedly a veteran of the first Tour of 1903, which he turned up in the Midlands. By lucky coincidence, I was able to track the machine down and photograph it for this article, and I can back up the book's account -- although I'd like to challenge Woodland's findings, and indeed the notion of progress in cycling which he presents.

Woodland tends to view bikes like this one as primitive. This view is only half right. Certainly, the steel componentry must weigh a ton, and the 46" wheelbase does not make for snappy handling. But then, the forgotten racer who supplied that third-hand quote was, to all intents and purposes, an offroader. His bike would have resembled this one, having more in common with the machines on 63xc.com's Rides page than with, say, a Trek Lance Armstrong clone.

Woodland calls the bars 'old fashioned' by comparison with the drops which were then appearing on the track. Fair enough -- but, cranked up to saddle height, those flared ends would have allowed the rider to keep his wrists relaxed across miles of bad road. Similarly, the heavy, stretched-out steel frame, typical of the roadbikes of the day, would have absorbed shocks that a modern lightweight would send straight up the seatpost. Incidentally, the clumsy-looking 28 x 1 3/8 tyres work out around 700-35c -- not that far off an Avocet. Gearing -- or lack of it -- is a thornier issue. We know that Desgrange stood out against the use of derailleurs for decades, and that, in the year he finally gave way, Roger Lapébie won the Tour on a gearie bike. But when the race began a generation earlier, gearing of all kinds was inherently suspect. The event was in its fourth year before a competitor risked riding on one of the new-fangled BSA freewheels! Woodland quotes a 1920 report from one Vernon Blake detailing a gear setup which would make good sense today: a flip-flop hub with 65" and 48" gears, often double-fixed, but with many riders preferring a freewheel on the larger cog for fast descents. This last presupposes the availability of good braking, however. The 1903 bike lacks brake mounts of any kind, perhaps because its owner rated the safety of pedal braking above that of the primitive brake mechs then available. The 1903 bike was an upscale product from an industry that had been in existence for well over thirty years at the time of its manufacture. Rather than viewing it as a half-baked forerunner of contemporary roadbikes, therefore, I think it is more useful to consider it as a machine built optimally using the technology of the day for the road conditions which then obtained.

Woodland considers those unadopted roads of the young century 'appalling'. I disagree. To me, as to many cyclists, they sound like a lost paradise, and the emergence of the automobile among firms that previously made bicycles seems a painful irony. Around here, then, Mr Woodland and I part company, he choosing the metalled roads, I the tracks and bridleways. But it was fun to listen to his tales of those first 30 years, and I recommend his book wholeheartedly. [ TOP ] |

Writer

Will Meister ventures onto C-roads only when forced to do so.

Date

v1.0 written October 2005

Related

Les Woodlands 'Unknown Tour de France' is in stock at Amazon.

Photos of the 1903 bike are courtesy of Richard Eaves, the present owner. Mr. Eaves plans to sell the bike. Please contact us if you'd like to learn more.

Ancient tour photos are from the excellent Velo Archive.

Fancy trying flared bars offroad? Ask Matt.

Mailing list

Join the 63xc.com list.